Most of us are familiar with the metaphor for America as a “melting pot.” People from countries all over the world come together here to form one nation where we are all Americans. This metaphor implies that during that process, our diverse backgrounds, cultures, and religions melt away as we form a homogeneous American stew.

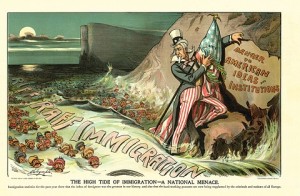

America was founded by a group of Europeans who pushed out the natives of the New World so that they could establish their own society. With an already pre-determined idea of what an American should be, immigrants by the Nineteenth Century were subjected to nativism, the fear of foreign ideas and influence in favor of those of the “native” population. Immigrants were thought to have radical ideas that were influenced by foreign thought and foreign rulers.[1] Every group of people that arrives in America has to undergo an “Americanization” process. This process consists basically of assimilation into mainstream American culture.

The metaphor of the melting pot has shifted. America is now to be considered a “tossed salad.” This means that components of our racial, religious, and cultural heritage remain intact. We identify with our groups outside of being just plain American. We are Mexican-American, African-America, Muslim-American, Italian-American, Asian-American, and the list goes on.

Immigrants play a balancing game. They struggle with figuring out what parts of their culture to keep and which should be discarded in favor of assimilating with American practices. Even though, in theory, we celebrate the diversity within America, there is an othering that takes place for immigrants who do not fully assimilate.

In Edwidge Danticat’s short story “Caroline’s Wedding,” discussed up some of these issues. Grace and her parents are immigrants from Haiti, with her younger sister being the exception having been born on American soil. Much of the tension within the family stems from the difficulties of being immigrants and the varying levels of assimilation to American culture.

Ma has much stronger ties to her Haitian culture and is reluctant to let those go. Meanwhile, she has trouble adapting to the behavior of her daughters, which is much more “Americanized.” The main point of contention is Caroline’s engagement to Eric, a Jamaican. She disapproves that Eric and his parents have not come to her to ask for Caroline’s hand in marriage. Ma is discontented that the old Haitian ways are not practiced. “When we were children, whenever we rejected symbols of Haitian culture, Ma used to excuse us with great embarrassment and say, ‘You know, they are American.’”[2]

The Lower East Side Tenement Museum is dedicated to addressing issues relating to immigration. Their program, Kitchen Conversations, aims to allow people to articulate their views about immigration and engage in a dialogue. These facilitated discussions allow a space where people can share, with other and maybe even themselves, their opinions and beliefs and be heard, maybe for the first time. Facilitators are there to challenge participants to evaluate their opinions and examine the origins of these notions.

“’If they insist on living all together with other Chinese people, they’ll never learn English. If they don’t want to be part of us, why did they come?’”[3] This outburst came from an exasperated participant in a Kitchen Conversation. The idea that the lack of assimilation is a sign of lack of wanting to be in America, ability to be a loyal citizen, and devotion to the ideas in the Constitution. Yet when questioned about what assimilation means, many participants disagree.[4] What does it mean to be truly American? Grace grew up in America along with her sister, but what makes her sister so much more American than her? Grace only felt validated once she received her naturalization papers. “I felt like an indentured servant who had finally been allowed to join the family.”[5]

Immigrants struggle to merge two identities. With America’s immigration population is projected to grow staggeringly by 2050, we need to start to challenge our notions about immigrants and promote tolerance.[6] What it means to be “American” is changing and maybe it’s time we start to truly embrace America as a tossed salad.

[1] Higham, “Patterns,” 4.

[2] Ewidge Danticat, “Caroline’s Wedding,” in Krik? Krak!, INew York: Vintage Books, 1996), 215.

[3] Ruth J. Abram, “Kitchen Conversations: Democracy in Action at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum,” The Public Historian 29, No. 1 (Winter 2007), 60.

[4] “Kitchen Conversations,” 72.

[5] “Caroline’s Wedding,” 214.

[6] Jeffrey S. Passel and D’vera Cohn, “U.S. Population Projections: 2005-2050,” Pew Research Center, http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050/ (accessed February 4, 2014).

No one seems to know what being an American truly means. Case in point, I studied abroad in Mexico as part of an interview project for American deportees. My colleagues and I were shocked when a middle-aged man stepped forward and spoke to us in fluent English in a distinctly Californian accent. He never obtained his papers, although he had been in the United States for almost his whole life. He had two children, American born, who did not speak Spanish. Yet the whole family was in the heart of Mexico, and could not cross the border again. Is he American? The government says he isn’t, even when he is a textbook melting pot case.

Your statement about promoting tolerance and challenging our notions about immigrant reminded me of the current controversy happening with Coca Cola right now. During the Superbowl Coca Cola aired an commercial in which America the Beautiful was sang in seven different languages. (you can watch the video here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=443Vy3I0gJs) Social media instantly blew up with responses to the commercial, many of them negative and intolerant. It was a sad showcase of the intolerance of many Americans. If you are looking for more information on this controversy I recommend checking out an article on Time Magazine’s website. (http://entertainment.time.com/2014/02/02/coca-colas-its-beautiful-super-bowl-ad-brings-out-some-ugly-americans/)

My favorite part about the controversy is how people are whining that the National Anthem should be sung in English, but America the Beautiful isn’t the National Anthem… This reminds me of a personal experience. There’s a big group out there that believes if you don’t speak English, or if you don’t speak English well, you are unamerican. When I worked the front desk to a real estate office I remember encountering a man with a heavy accent. He said he was American as of a few months prior. I believe that means he passed the test and got his papers. When I asked where he came from he became angry and insisted he was American. I don’t want to think he was ashamed of his past. Perhaps he was frustrated that the government recognized his citizenry while other Americans treated him like a second class citizen. I had never considered the innocent question, “Where are you from?” to be a sensitive topic to immigrants until after that moment. Now I am more careful.

I actually tweeted about this earlier in the week! Timely, huh? One of the things that came out of the discussions, with Glenn Beck leading the charge (go figure), was a fear of multi-culturalism and how this has “ruined” other western nations. This argument suggests that there is no unified culture or common ground and because of this we are a divisive and weaker nation. Which is so interesting because I think we often forget how this nation was founded. This goes back to Emily’s point that this is a nation of immigrants and always has been.

Exactly. I feel like the dialogue programs at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum do a good job of bringing some of this out. When we remember that all of us have differences, including different cultural and ethnic heritages, it seems easier to accept the differences of others. And once we start talking about our differences, we realize that we actually all have a lot in common and also that these differences have, and still do, make America a stronger nation.

There is a common objection to the toss salad that’s worth addressing. I have met people of various ethnic and racial backgrounds who are concerned that our society can’t be unified unless it’s a melting pot. This always sounds like a racist objection–and it often is–but I’ve been surprised by how many people I’ve met who voiced it without having antagonistic feelings towards anyone. They’re genuinely concerned about our society’s ability to hold together if assimilation isn’t encouraged. I like to tell them about how the Pennsylvania Dutch didn’t assimilate for a long time, but they were still a functional part of society. They retained many of their cultural traditions, and even developed some new ones in the United States. They were not mainstream Americans, but they were no longer Germans either. They were something unique, and wholly American. Maybe current immigrant groups will end up in the same unique position some day. This example often satisfies those who are concerned about national unity.

I have often thought how it is interesting in many cases that what it means to be American is solely defined by the language that we speak, in this case English. For many people, to be an American means you assimilate, and in my experience and conversations with others, that always meant that immigrants learned to speak English. Recently, I started doing some ancestry research and found that not long after one ancestor arrived in America, he took the oath of allegiance, learned to read and write English, purchased land, and served in the Revolutionary War. This all occurred within 4 years of arriving in Philadelphia from Germany. It was interesting to learn what assimilation meant to him.

I think that objects can demonstrate how the US is a “tossed salad.” I know that there a few objects that embody my grandfather’s experience of immigrating to the US from Russia. For example, when he and his family arrived at Ellis Island, they brought the family samovar (picture: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/55/Fomin_samovar.jpg)–a container used in eastern Europe to heat water–with them. They used it when they first settled in the Lower East Side and, eventually, Brooklyn. Years later, when my grandparents raised my father in Queens, my family enjoyed the samovar for aesthetic–not functional–purposes. Regardless of how it was used, the samovar has important meaning for me now, especially as an object that connects me with my family’s cultural heritage.

Both tropes, “AMERICA AS MELTING POT” or “AMERICA AS TOSSED SALAD,” are essentially part of the same narrative, “AMERICA IS A NATION OF IMMIGRANTS.” But wait. There are lots of groups who do not fit into the “immigrant” definition. Native Americans, enslaved African Americans and Caribbean Americans, conquered people within our Empire.

I like that your brought up the theory of ‘othering’ that happens when immigrants do not fully give up parts of their culture to assimilate into American society. If America is said to be a tossed salad, shouldn’t immigrants keep these aspects of their culture to add to the diversity in American culture? I do not think anyone can be truly American as there is no one type of American. Each of us have different sets of principles that we were raised by that influence/shape the way we do things. In addition, we all speak differently, depending on many factors such as region, location, and culture. To say that there is one type of American will be an outright lie.

The Kitchen Conversations article brought up the issue of language as a barrier to assimilation. I think it is important to remember that America has no national language. ESOL classes are essential to offer immigrants the tools to interact with many people in this country; however, knowing English is not always necessary, as the article brought up. Does the burden need to be on immigrants to assimilate to American culture, or should Americans make more of an effort to learn about other countries, cultures, and languages?

You bring up a great point, Kirsten. Part of the beauty behind the mission of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum is the attempts to make ESOL classes more accessible to people. The belief that there should be “requirements” to become a part of a culture ignores the real truth that everyone in a given place, no matter what language they speak, creates, maintains, and contributes to the culture of that place. What we can do, as members and staff of community organizations, is ensure that everyone has the opportunity to succeed. And that means meeting people on their level, getting to know their lives, their cultures, their places of origin.

I know that this conversation has been discussed endlessly, but it is still valid to bring up here. Since English is such an important language for global business negotiation it is being taught in schools in a variety of other countries around the world. In Europe, for example, it is not uncommon that many people in countries like Germany, France, Italy, etc. have a decent understanding of English, even though that is not the primary language in the country. Our dependance on English is very apparent when traveling to any of these places and observing how many people can speak both English and their primary language. The business significance of English is partially responsible for this phenomenon, but it should not be an excuse for Americans to give up or openly reject other languages. If immigrants are the only ones expected to work hard to learn a new language, why aren’t we more sympathetic towards the challenge learning a new language (while simultaneously adapting to a new culture) entails?

Araya, I agree with you that “there is no one type of American.” I do wish that people coming to this country, in the past, present, or future, could bring their cultures and religions and traditions with them and not be afraid of being ostracized or criticized. I love doing genealogy, and reading this post and its comments is making me think not just about my individual ancestors, and the facts about their lives, but where they came from, and what traditions they might have brought with them that were lost between then and now.